(C) Najmeh Khalili-Mahani

Before the COVID19 Pandemic, many of us were stressed by screen addiction. So stressed (see footnote below) that the Quebec’s Ministry of Health and Social Safety (MSSS) was holding expert’s discussion forums to address concerns of parents about screen use by children between the age of 2-25. On March 20th, we were called back to discuss the benefits of screen usage for this young population. Ironically, that conference may no longer be needed. COVID19 has made a compelling case.

During the COVID19 Pandemic, digital literacy has become an essential competency. We should not have any human contact. Premier Legault just talked about the irony, for parents who have always asked their children to get off of screens, to have to now encourage the youth to remain glued to screens, and to find fulfillment in many possibilities afforded by the social media.

After the COVID19, we will be forced to embrace all our our ambivalences about screens. Our future screen-related stress will be the unavoidable reality of the Digital-of-Everything at the speed of electrons, and joining China, Israel, and Iran in adopting their surveillance systems of public safety.

To navigate this stress, we may go back to Marshall McLuhan’s Theory of New Media, Inspired by Hans Selye’s Theory of Stress.

In Understanding Media: Extensions of Man, Marshall McLuhan suggested that all screens are initially stressful but we must consider the nuances of screen-related stress. He urged us to study media’s impact on our self and the society in the same way that the notable physician, Hans Selye, examined the stress theory of illness

In a 1936 Nature publication, Selye defined stress as a quantifiable “general adaptation syndrome“–a cascade of common physiological responses to different ‘alarming’ stimuli, which help the system to adaptively recover its equilibrium–else, fall to disease.

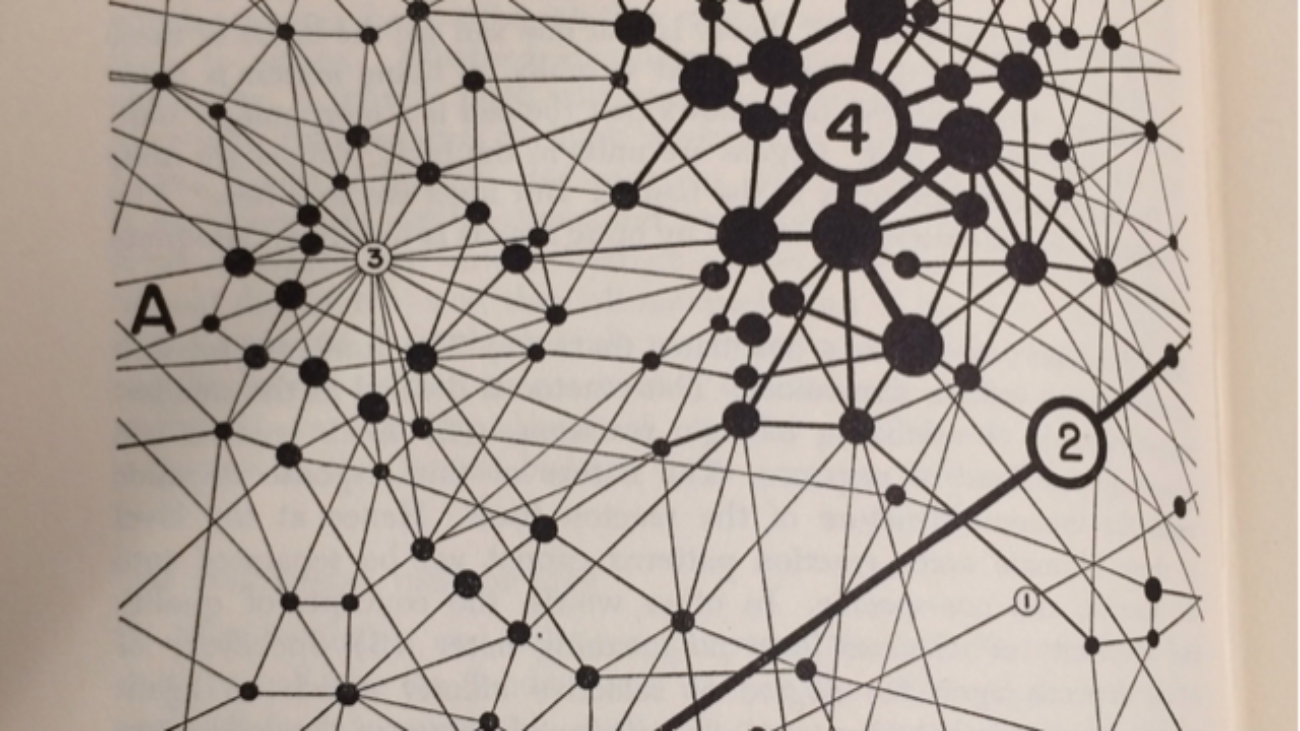

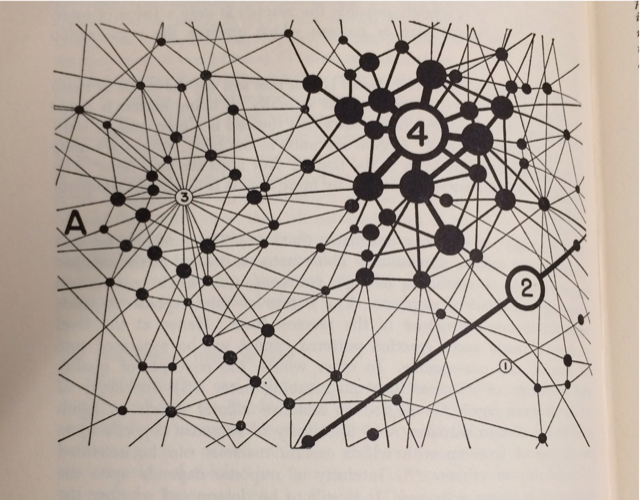

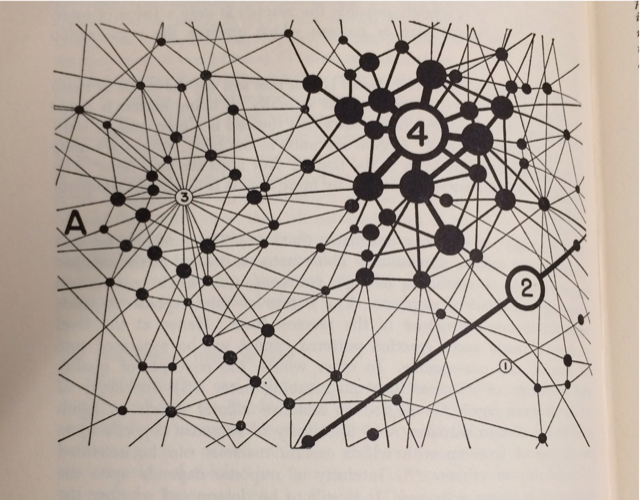

Writing for the first issue of the Journal of Explorations: Studies in Culture and Communications (edited by McLuhan), Selye depicted the living organisms with a network diagram of node (See figure below. Reactons or units of life). The nodes were “associated with eachother by interactions of varying importance”.

Pressure exerted on any unit would spread through other nodes, depending on the degree of its connectivity.

Figure Caption: Selye’s depiction of ‘reactons’ (units of life) and how stress exerted its specific and non-specific effects by the degree of assosiation between the communication networks of the body. (Source: The Stress of Life).

McLuhan and Selye’s theories would have treated screens as both stressors and de-stressors in finding adaptive equilibrium.

In his 1956 book, Stress of Life, Selye wrote:

‘Stress is the nonspecific response of the body to any demand, whether caused by or results in pleasant [eustress] or unpleasant [distress] conditions.” But eustress causes less damage because ‘”how you take it” determins whether you can successfully adapt to the change.’

McLuhan concurred:

‘Physiologically, man in the normal use of technology (or his variously extended body) is perpetually modified by it and in turn finds ever new ways of modifying his technology. Socially, it is the accumulation of group pressures and irritations that prompt invention and innovation as counter-irritants.’

For McLuhan, electronic media ‘stressed’ our sensory systems, and spread the effects through the nervous system to the rest of the brain and body. The sensory system had to process the fast, sensorially intense, and fragmented content transmitted through the audiovisual senses. The brain had to make meaning of what was communicated.

McLuhan used Selye’s approach to explain how media (be it road, print or electric media) was an extension of our body–a response to the need for more power and speed. “Every technology”, he wrote, “creates new stresses and needs in the human beings who have engendered it”, thus perpetuates a need for new technologies for adaptation:

“When a community develops some extension of itself, it tends to allow all other functions to be altered to accommodate that form”.

McLuhan translated the biological model of stress and wrote:

“[I]n operating on society with a new technology, it is not the incised area that is most affected. The area of impact and incision is numb. It is the entire system that is changed.”

For Selye, stress was not a necessarily bad reaction, but an adaptive and corrective response to ensure organism’s survival:

‘It is through the general adaptation syndrome that our various organs–especially the endocrine glands and the nervous system–help us both to adjust to the constant changes which occur in and around us and to navigate a steady course toward whatever we consider a worthwhile goal.

Interestingly, at the level of psychobiology, we find robust correlations between psychological stress and screen dependency, For instance, in a cross sectional survey of 654 adults we found that more than 95% of the responders depended on screens for communications and information, but smartphones, social networking, entertainment and relaxation were proportionately more important to those who were stressed and considered themselves screen addicts.

We found that the pattern of relations between different types of screen use (for work or for play) and different type of stress (emotional, or life-related) were complex and needed nuanced interpretations.

If screens were causing (emotional) stress, then we expected that those who used them for work or for seeking news and information to have higher stress levels (emotional, perceptual, life-related or healthwise). But that was not the case. All groups were heavily and equally dependent on using their screens for those activities. On the other hand, if screens were used for coping with stress, then we expected that those who were more stressed to use them for entertainment and relaxation. That was the case.

We hypothesised that there is perhaps a silver lining if screens provide a refuge from stress.

To think that heavy dependence on screens for entertainment, relaxation and social networking reflects a coping strategy to cope with existing stress through distraction, self-care and support-seeking is plausible, and our survey, Coping with COVID19: Which Media Are Hurting, Which Media Are Helping, may reveal that indeed there is a causal relationship between being stressed and using screens for relief.

While the Premier of Quebec is asking us to enjoy screen addiction in order to limit the spread of COVID19 many of us are thinking about the inevitable leap into an existential polemic: “The Digital of Everything.”

Until now, the majority of us have been worried about the implications of screens on our mental and physical health.

Like all technologies, they have increased physical hazards: Increased number of road accidents due to distracted driving, carcinogenic risks of radiofrequency electromagnetic exposure, effects of blue light on our sleep patterns addiction to television (when it was introduced, and now), addiction to video games, addiction to The Internet, and to mobile phones, etc.

We have also worried that social media may create psychopathology, violet teenagers, obesity or ADHD.

But now, the COVID19 pandemic has shrunk all our degrees of freedom in the global village, because of the global village.

The unforeseen quarantine we find ourselves in demands us to develop technologies to liberate us and our economies from this mysterious virus.

We may soon agree to join China, Iran and Israel in drone-shaming those who break quarantine. We have long been praising self tracking and biosensors, and will be communicating even more omnisciently: face tracking , movement tracking, body heat tracking, , teleworking, tele-schooling, tele-caring, etc.

How will these forthcoming screen(ing) technologies of (bio)communication stress us?

In The Laws of Media (1988), Marshall and Eric McLuhan proposed a tetrad model of media to guide how to study new technologies by asking four questions:

- Which sense or function does it enhance?

- Which sense does it render obsolete?

- What older, previously obsolesced grounds does it bring back to service? and,

- What happens when it is pushed to the limits of its functionality?”

In Gutenberg Galaxy (1962), Marshall McLuhan, showed how the print and typography caused a visual stress by forcing the man to limit their field of view into abstract alphabet, in exchange for creating a system of communication that could be transported and could exist outside the body of the story-teller. “The print-made split between head and heart is a trauma”, he wrote, “which affects Europe from Machiavelli till the Present”.

McLuhan celebrated the audiovisually liberating possibility of electronic media:

“[W]e can now live, not amphibiously in divided and distinguished worlds, but pluralistically in many worlds and cultures simultaneously (…) The new electronic interdependence recreates the world in the image of a global village.”

But the future systems of communication will not be communicating the projections of our “selves” into sounds, texts, or images. They will be turning us inside out: no gene, no sweat gland, no heart beat, no respiration phase, no body temperature, no facial feature of pain or joy perception will be masked or hidden.

Before COVID19, our Machine Agencies group were pondering about the ethics of surrendering to the artificial agency of the machine. We were criticizing the surveillance capacity of the forth wave of industrial revolution, to be unleashed with the 5G and Internet of Things (IoT). But the future has arrived.

The media has become the message, in its most bio political capacity, as our global village is rising walls not only between our countries, but also between us, in the same house, self-isolating, with the intension of liberating us from the fear of the virus and the pain of isolation, with technologies of self-communication.

In a 1945 issue of The Atlantic magazine, Vannevaar Bush, the pioneering American inventor and the head of National Science Council in the US, promised that science and technology will make it possible that the memories of generation, and the sum of their knowledge could be preserved, and synthesized through electronics capable of recording and deconstructing linguistic, photographic and computational relations among information entities—memory indices, which he called Memex.

We have long passed that stage.

Inter-netted, engineered to be ‘smart’, with an incredible capacity to hold memories (pictorial, textual, audio, recently even bio-sensorial), and wired to process and retrieve at the speed of light, we have long been aware of what senses they were numbing, which forgotten or hidden memories they were digging, which barriers of privacy and imagination they were breaking. This sensory numbness had given us reason to join Douglas Rushkoff (the media theorist and cyberculture author) on Team Human to rescue our humanity.

According to Selye, any external nocuous stimuli caused alarm (the body detecting the threat), put the body into reaction (the body trying to adapt to the threat) and finally settled on recovery or exhaustion (depending on whether the adaptation was successful or not).

This massive general therapy (locking down the entire world), to which we consented for the greater good of the vulnerable, will have compromised our immunity authoritative norms–just as stress may do.

Those of us who work digitally, and robotically are untouched. The rest, including those in the first line of defense (doctors and nurses) are not. We are now asking the third question of McLuhan’s tetrad laws of media: What older, previously obsolesced grounds will the new technologies of surveillance bring back to service?

As McLuhan suggests, every invention is to replicate us, replace us, with a version with enhanced, unbreakable, extended senses.

Even before the Pandemic, our global village was stressed by N.U.T.S: Novel, Unpredictable, and Threatening conditions, that challenged our Sense of control. This is why we have been inventing screens and ICTs, more than ever, to take comfort in being omniscient controllers of the world that is challenging our sense of self, physically and psychologically.

The proponents of the Digital, have been urging us to reconnect with each other, and with our humanity. Rushkoff has been pleading with us to Program or Be Programmed.

But in the aftermath of COVID19 outbreak making it a social responsibility to socially distance and self-isolate ourselves for the greater good of the humanity, is it even possible to avoid promoting pervasive ICTs that enable us to care for those from whom we are cut off physically?

I believe this is the precise moment that our Stressed Systems, which are in heightened reaction mode, must find a quick path to recovery, because the senses that the technologies of surveillance will numb, are the core of our SELF. This is the moment to ask the 4th question of the tetrad model: What happens when it is pushed to the limits of its functionality?

We all want progress, but if you’re on the wrong road, progress means doing an about-turnand walking back to the right road; in that case, the man who turns back soonest is the most progressive. C.S Lewis